An Ethics of Black Queer Seeing

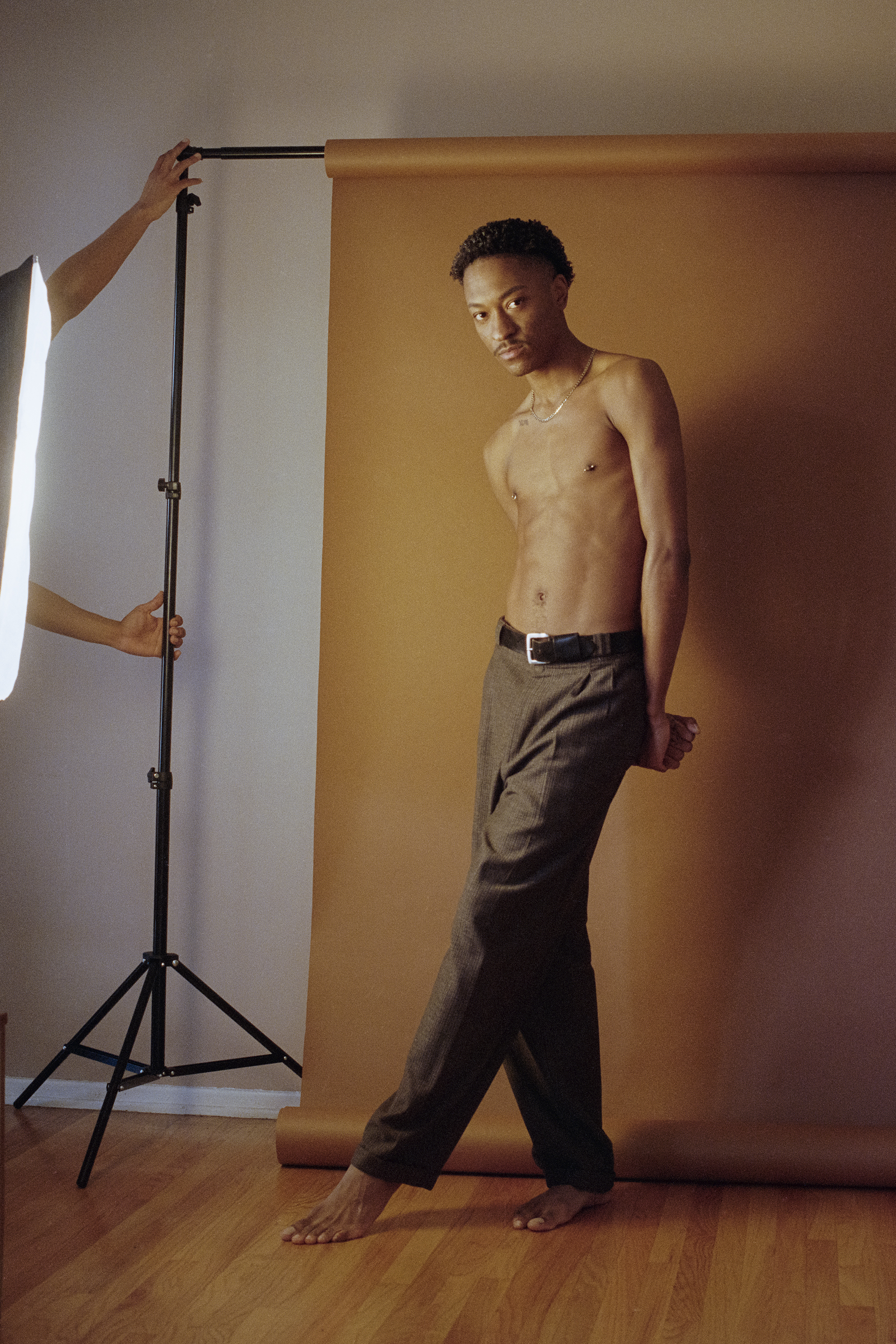

Clifford Prince King

J, 2020

24 x 36 inches

Canson Rag 310 GSM

Essex Hemphill, a singular Black queer poet and writer who succumbed to AIDS-related complications in the nineties, was a prognosticator. It was Hemphill who sermonized in his poem, “for my own protection,” in Ceremonies (1992), that

“the lives of Black men are priceless/and can be saved. We should be able to save each other.”

Clifford Prince King’s exhibit, “Yesterday and Beyond,” is but one visual enactment of Hemphill’s articulation.

King’s images summon our attention away from that which tends to be used to constrict and define the lives of Black queer men by others’ imaginations, needs, or (sexual) desires…

In his work, Black queerness is untethered from that which awaits to destroy us—even if what awaits us sometimes are our own hands. In “Yesterday and Beyond,” however, Black queer men are documented and, yet, unbound by normal limits. In the works, I see King and Hemphill. And I am seen. The images are beautiful. I like what I see.

As I peer into the house captured in the photographs my eyes center, at first, on the gable and its stunning A-shape structure organized around a set of windows.

Clifford Prince King

I Told My Baby to Meet Me on 24th Street, 2020

48 x 32 inches

Canson Rag 310 GSM

The house itself is charming and it’s adorned with detailed woodwork. But I am most captivated by the windows. Behind it stand two people—Black men, presumably. Both are donning durags. Both are enraptured in an embrace. The hued warmth of the image is matched only by an incandescent intimacy. Both are kissing with just enough space between their seemingly naked bodies to see a glimpse of the room in which they are situated—the men become our window.

Clifford Prince King Last Door Down the Hall, 2022 48 x 32 inches Canson Rag 310 GSM

The men are home or, rather, at home in a site of domesticity. Behind closed doors, where pleasure may well be safe. Not the doors of a closet, but those we build around ourselves, each other, and our communities, for our own sake. The time and place could be somewhere in the past or figure as a vision of that which might exist in the future. Such opacity of time and place is important when recognizing the narrow representational landscape in which Black queer men tend to be imagined. We are thought to exist in the world without safety within and without the home. But in King’s body of work we are invited to stretch, and reach past, the borders of our imaginations and senses of time.

We are invited to gaze up on Black queer pleasure, connection, touch, and aliveness as it exists within and beyond linear time.

Each photograph reverts, and dismisses, the gaze that is otherwise overly fixated on white and heterosexual acceptance and normalcy. The photos are texts that attest to our existence as human beings, and not subjects, with textured lives. Black queer men bare.

Black queer men braiding the hair of another while smoking a blunt. Black queer men standing before a window or mirror bare, with their dicks hanging and asses in our faces, unashamed.

But unlike some uses of a naked black male form, these bodies don’t seem to invite the viewer toward sexualization. They aren’t concerned with us; they are only present with one another.

Clifford Prince King

Safe Space, 2020

48 x 32 inches

Canson Rag 310 GSM

Clifford Prince King

Untitled, Unknown Boy, 2018

30 x 20 inches

Canson Rag 310 GSM

King's images are visuals that remind us that our “seeing” does not have to be shaped by the material forces of a white, male-centered, heteronormativity that besieges us.

We are not Robert Mapplethorpe’s subjects. We are our own.

And they are the types of made-images that I longed for coming of age Black and queer in a world where I did not always know that we existed in our fullness. Not because we have not been here–meaning alive and present in our homes and the world–but because we have existed in a world that favored our invisibility and, ultimately, our illegibility.

This is why I take umbrage to Susan Sontag’s declaration in her first fictional work, The Benefactor (1963), where she writes, “Life is a movie. Death is a photograph.” Death to whom? To the overly represented? The death of those whom a white, non-queer, majority have already factored as the socially dead?

Clifford Prince King

Mount Morris Park West, 2021

24 x 36 inches

Canson Rag 310 GSM

King’s photographs, at least for those who are owed legibility, are not the places we go to die. They render the existence of Black queer life and portend futures “not yet here” as the beloved queer theorist Jose Esteban Muñoz evangelized. King’s works are a testament to our being and our being here and there. The photograph, especially when made by artists like King, who practice by way of what Sontag names an “ethics of seeing” in her essay, “In Plato’s Cave,” are made with the care and an attentive protection of the Black queer men in them as sentient, sexual, people.

A Black queer ethics of seeing demands that photographers not situate themselves outside of the art that they are making (whether they physically appear in the works or not).

And it requires a type of self-reflexivity that allows the artist and audiences alike to acknowledge their presence in the very material structures that contain, or constrain. King situates himself in some of the works as a participant documenter.

Are those his hands positioned on the lips of the other man with care? Is that his naked body reflected in the mirror opposite the naked body of the concealed sitter?

Clifford Prince King

Our Last Blunt Together, 2019

30 x 20 inches

Canson Rag 310 GSM

Clifford Prince King

Circuit, Atlanta, 2021

24 x 16 inches

Canson Rag 310 GSM

King’s work is grounded in a Black queer ethics of seeing and care centered on the very protection of the people he captures in real time, which can be interpreted as occurring in the past, present and future.

This is what it means to love Black queer men: to be represented, remembered, or projected into the future is, in fact, an act of care and also one of pleasure.

Clifford Prince King, Clifford Prince King

Plymouth, 2021

24 x 16 inches

Canson Rag 310 GSM